Cortázar: Between Worlds

Explaining Julio Cortázar and his ideas of living, becoming and other discussions.

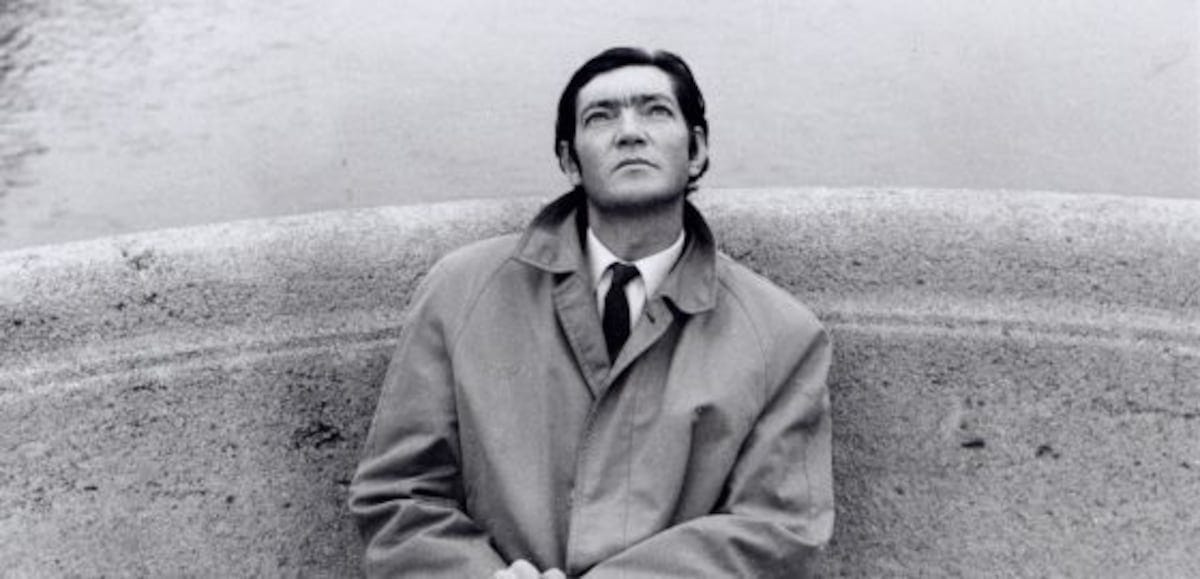

In the large space of Latin American Literature, few figures stir the pot and navigate the seas of intimacy and its paradoxes, one notable one is Julio Cortázar. Acknowledged and celebrated for his formal experiementation and dip philosophical questioning, Cortazar wrote stories but he too rearranged the boundaries of what literature means to others, and what it ultimately meant to him. Beneath his literary reputation as a “master of surreal” there was a clearly intellectual thoughtful mind who held love and friendship to a high statue, often calling back to it as two parts of the same existential yearning. His special bond with poet and contemporary Alejandra Pizarnik would be most indicative of the type of value and care he would put into friendship. This then helping us understand his views on human connection, as complex, somewhat unfinished and always…becoming.

Cortázar didn’t usually write from a place, and he did not live fully at one place either. Born in Belgium and later, raised in Argentina, later to be exiled in France. His writing would drift between continents. To best describe Cortazar would be to explain him as an in betweenness. His works revolving in curiosity, as his characters too wander and his continuous stream of thought resisted conclusion. He didn’t necessarily seek clarity, rather disruption. To not be fixed in reality, but a truth found in fragments of joy in life.

His works rise from the intersection of an intellectual’s plate of thought: philosophy, politics and poetics. He belonged in a rather special generation of writers that can be classified as a Boomer era of thinkers, with contemporaries like Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Mario Vargas Llosa and Carlos Fuentes. He took space with his unique perspective, where others thrived in realism and magic, Cortázar drove his work in the ordinary life and its existential oddities. He made the surreal follow a logical walk, as in his world the logical could sweep itself into deeper chaos.

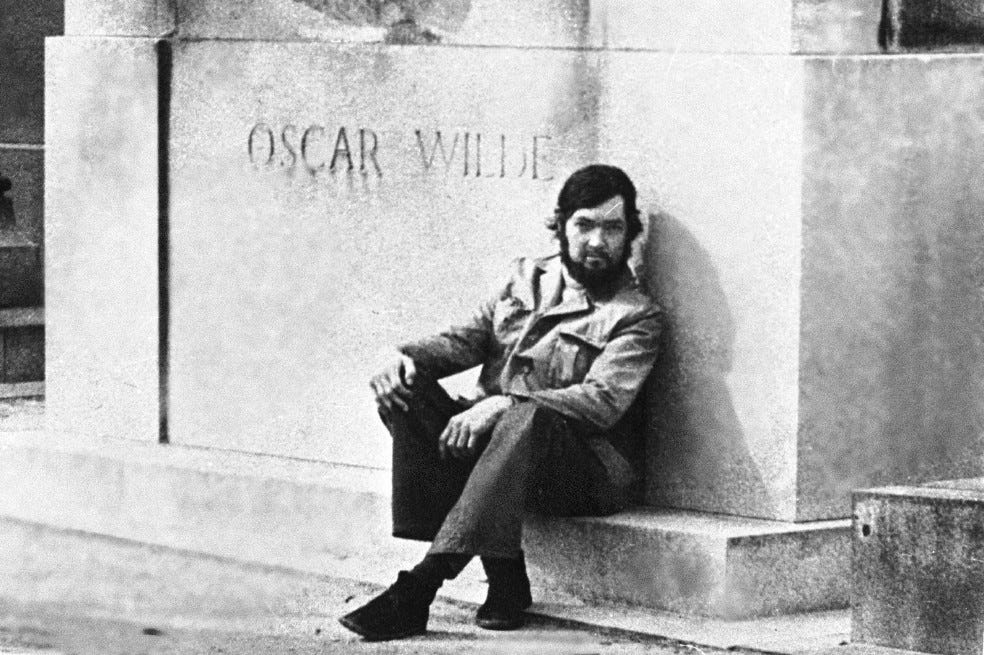

When Cortázar moved to Paris, France in 1951, he moved into a metaphysical shift of sorts. This would be after leaving Argentina at the rise of Peronism as his frustration with political discourse and experience constrained his artistic freedom. Like many other exiles, he carried a sense of home in the syntax of his works. Being away from home would mean finding a sense of it anywhere else, and Paris would give him a backdrop to reconsider his identity, remain culture and compose time. Argentina in his mind, and a reconstruction of what home was in the distance in France.

Living as a literary expatriate would give Cortazar the freedom to live outside of the often conventional, his works would mirror more closely what the embodiment of resistant meant for that new age of intellectuals. Writing in cafes, wandering the Left Bank and immersing himself in the different scenes of music, notably the jazz scene in Paris. While the immersion felt encouraging, he wouldn’t fully feel part of the European culture, as a matter of fact, the sentiment of feeling out of place and never fully something accompanied the writer. His fiction works thread this liminal space, resonant to the Latin American context, in Parisian form and yet, universally felt.

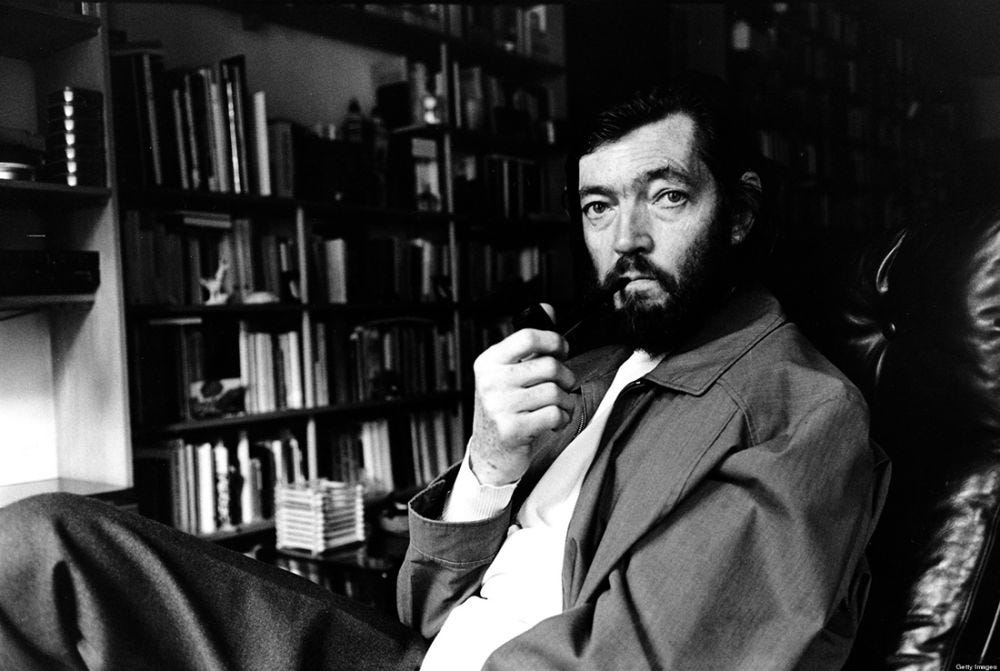

In Around the Day in Eighty Worlds (1967), his a hybrid work of essays and observations, he shows his astute views of life as a writer. It was not a matter of profession, rather a “spiritual” calling. “The task of the writer,” he once wrote, “is to name what has not yet been named, to make visible the invisible, and to interrupt reality long enough to ask: is this the only world possible?”

Nowhere is Cortázar’s literary ethos more fully realized and expanded than in his undeniably influential Rayuela (Hopscotch, 1963). Rayuela is a labyrinthine novel that offers multiple entry points and a unique structure. It invites the reader to "play" with the book and to skip chapters, read in alternative orders, and break free from monotony. However this is not a gimmick. This is a metaphysical assertion. Cortázar saw existence as a circle, pattern, or hopscotch grid drawn on a cracked sidewalk, rather than a line. This could be interpreted as the way the he understood his own path in life. We understand more closely with Horacio Oliveira, the novel's disenchanted protagonist, wanders across Paris in search of meaning, love, and a language that would not betray him. He is the archetypal Cortázarian person, torn between intellect and emotion, philosophy and foolishness, desire and detachment. Cortázar's fundamental concern becomes apparent in him: how can we live truly in a world that expects us to pretend?

In this case, Rayuela is far more than solely a narrative disruption. It is about existential rebellion. It contends that our inner lives are significantly more chaotic, richer, and less obedient than the social systems designed to confine them. To appreciate that turmoil, Cortázar wrote books and stories in which we might feel our way through them rather than merely think about them.

Cortázar's works explore the transient qualities of time and identity. In "Axolotl," the narrator transforms into a tank-dwelling Mexican salamander. In "The Night Face Up," a man switches between modern life and Aztec sacrifice, blurring the divide between dream and reality. These are not only surrealist flourishes. They are existential exercises that investigate what occurs when we let go of reasoning and allow our unconscious to emerge. He held faith in the permeability of the self. He did not believe love was about fulfillment or certainty. It was about closeness with the unknown, a way to be close but not possessive. He once observed, “Only in love do we see the other as an absolute mystery — and still insist on staying.”

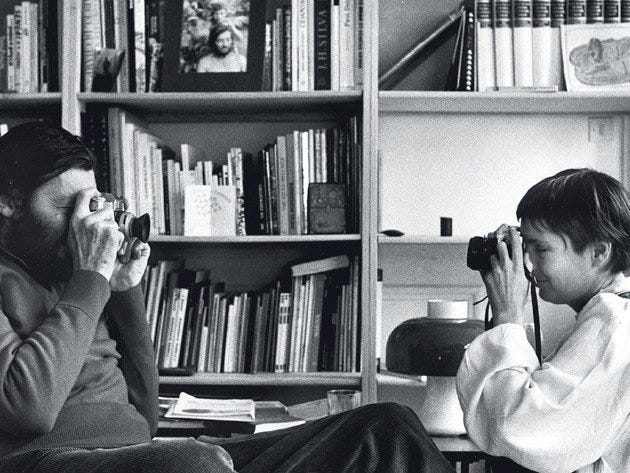

He exchanged letters, tenderness, and emotional connection with poet Alejandra Pizarnik, (a relationship more closely ambiguous in nature or romantically in other interpretations) indicating how this perspective infiltrated his friendships. Cortázar's conviction that that connection is an act of art, a kind of mutual translation between souls.

Early in his career, Cortázar was often viewed as apolitical, but his time in Paris progressively influenced him to become more activist. He became more outspoken about injustice, censorship, and imperialism after living through the aftermath of the Algerian War and then seeing the horrors of dictatorships in Latin America. Later pieces by him, such as Libro de Manuel (1973), blended political intensity with experimental form. In spite of this, Cortázar rejected propaganda even in his most political works. He viewed literature as an instrument for waking rather than a megaphone. His mission was not to offer solutions, but to upend complacency and expose the ways in which the so-called "normal" world was based on forgetting, habit, and power structures.

His belief in liberty, and not just in the political sense, but additionally in the metaphysical and emotional senses is what ties all of Cortázar's writings altogether. To live completely was to live intentionally, to challenge the predetermined narratives, to reject the false dichotomies of identity and otherness, love and loneliness, and the binary between achievement and failure.

For this, Cortázar intended his novels to then awaken within his readers, not only make them satisfied. His writings encourage us to become disoriented, uneasy, and, in the end, realize that we are more complicated and independent than we have been taught.

Julio Cortázar continues to be an inspiration today for people who write in multiple languages, reside in somewhat of an exile or relocative state, and experience feelings of both excess and inadequacy. He makes it possible to remain incomplete, in progress and constant wander. He reminds us that in a world of spectacle and assurance, sometimes the most radical thing to do is to write without regret, feel abruptly, and observe attentively.

Author’s Note:

Cortázar’s “Rayuela” (Hopscotch) is one of my favorite books. I too relate to his navigation of identity. It’s interesting to note how when we move elsewhere, we can be more astutely attracted to make sense of the home we live behind at a distance.

Best,

David